Navigating Patient Advocacy as a Physician: What I Still Needed to Learn

About the Author: David I. Rappaport MD has been a Pediatric Hospitalist at Nemours/AI duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, DE since 2005. He is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College/Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He is known for his research in the care of children with medical complexity as they prepare and undergo surgical procedures.

During my 15-year career as a pediatrician, I have developed tremendous respect and admiration for parents and caregivers - especially those of children with chronic medical problems.

Most of these parents are incredibly detail-oriented, ensuring that their children receive the correct medication, the correct dose, the correct feeding, and so on. And with medical errors being the third-leading cause of death in the United States, they know that they must advocate for their children, as many cannot advocate for themselves.1

Working in a children’s hospital has only underscored this respect and admiration for the advocacy of family members. During daily rounds at our hospital, our medical team -healthcare professionals including nurses, residents, and medical students - gathers at the patient’s room to make medical decisions for that day. In “family-centered rounds,” we involve parents and caregivers - not just as bystanders, but as active participants in generating the medical plan for their child.2

As a father of two children myself, partnering with parents to ensure high-quality care for their children both in and out of the hospital brings great satisfaction. I always encourage medical students, nurses, and residents to view our patients’ parents as our best teachers. Especially in cases of rare conditions, the child’s parents often know much more about the condition than we do.

In the world of pediatrics, we sometimes note how much we share with those who care for geriatric patients. Just like children, older adults often need caregivers to work as patient advocates for them when they cannot advocate for themselves. Even certain medical conditions like urinary tract infections, nutritional concerns, and skin breakdown are common in both groups.

As my parents began to age, I became their primary caregiver. I started to recognize the importance of an organized, savvy advocate to help them navigate our healthcare system and keep them safe and healthy through quality health care. As a pediatrician caring for complex children, I knew I had a lot to learn - but even I didn’t realize how much.3

Here are a number of things that I, even as a physician, needed to learn to effectively advocate for my aging parents.

Getting Organized

One of the most important tasks in making sure that our loved ones get the care they need is to get their medical information organized.

When I became a primary caregiver for my parents, I realized that my father’s medication regimen was becoming more complex and he was having trouble maintaining an accurate list. Thankfully, technology like cellphone applications can help make sure medical information is portable wherever we go. Some of the strategies can be fairly old-fashioned, too, like a paper list with multiple shared copies.

The first task is to collect all of the patient’s information in one place. Keeping a list of medications, providers with contact information, and health insurance (including dental and eye care) is a great first step. For children with medical complexity, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Emergency Physicians have developed a form to keep track of this information (downloadable here). Some caregivers may prefer a homemade version, however, while very complex patients may require an entire binder.

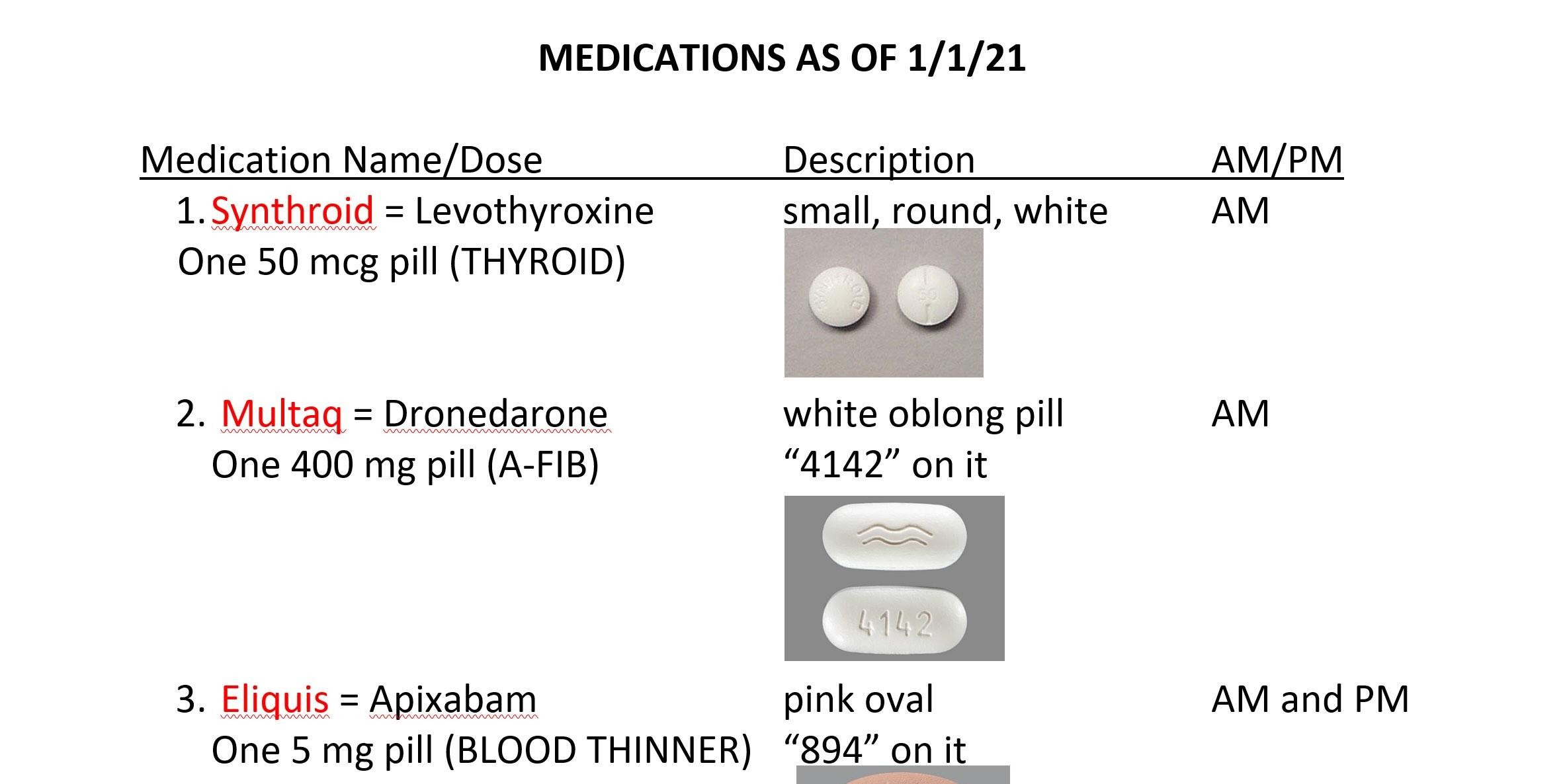

When making a medication list, it should ideally include medication names, doses, when they are taken, and photos of the medications themselves. Certain apps like the one included in Hero's subscription service can be helpful in maintaining an accurate medication list. Here is one paper example:

Photos can be especially important because patients will forget which pills are which. Many pills look similar to each other, and patients can often confuse generic and brand names for other medications. Moreover, certain pharmacies or insurance companies may change manufacturers over time, so the same medication may look quite different. Liquid medications can be even more confusing, especially if they are compounded or come in various concentrations. This medication list, combined with an updated physician provider list, will help all healthcare interactions be more effective and efficient.

The World of Medical Insurance

Keeping up with my parents’ medical bills was the second issue for me to tackle. Even for healthcare providers, the financial aspects of medical care in the United States can be perplexing. We learn surprisingly little about finances in medical school and residency, and what we do learn is on the provider and facility billing side, not the patient side. As a pediatrician, I especially knew little about Medicare, as very few children are covered by it.

The way insurance companies determine how patients are charged can be very difficult to understand. In the hospital, charges are often established by the chargemaster, a semi-secretive document that outlines hospital charges (though they are increasingly made public, such as in California).5 However, the chargemaster really only functions as a starting point for negotiations with insurers, so they are of limited helpfulness for the general public. These negotiations form the basis of how much patients pay for a specific health care service.

Entire books have been written about the finances of the American medical system. To advocate for a family member, one does not need to be an expert in medical finance, but must understand certain basic concepts such as deductibles, coinsurance, and copayments as well as systems like private/commercial insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans’ Administration.6,7

Communicating with and between Providers

The next issue I faced was coordinating my parents’ patient care. Since they lived in two areas, they had two sets of providers, one in each area, who rarely communicated with each other.

As patients become more medically complex, they usually see more providers, including primary care and specialist doctors, psychologists, therapists, and others. Although the primary care provider theoretically functions as the “captain of the ship,” this person cannot possibly stay up to date with the details of care and treatment options for hundreds, or even thousands, of patients. Communication becomes even more complex if the patient is seeing providers in multiple medical systems whose medical records do not interface with each other.

Patient portals may help communication between providers and patients, but these may not be included in their medical record or allow for thorough communication between multiple providers. As a result, keeping a file of updated medical data may still be required by the patient or their advocate. An active list of health concerns to bring to doctors’ visits can also help everyone remember the patient’s specific symptoms and conditions.

Electronic Medical Records: Not Always a Safety Net

For those of us in medicine who are old enough to remember care before electronic medical records, we know how problematic a handwritten system can be. Relying on handwritten medical notes and prescriptions is an ever larger setup for medical errors.

Consider the example of magnesium sulfate (“MgSO4”) versus morphine (commonly written as “MSO4”) - in this case, a prescription for a relatively benign laxative might be mistaken for one for a powerful opioid. Jokes about physician handwriting aside, these are easy mistakes to make! The Joint Commission, an organization that certifies safety in medical systems, even has a list of forbidden abbreviations to avoid these kinds of errors.8

Electronic medical records have their own issues, however. As a physician, I knew that depending on physicians’ medical records to ensure patient safety was sometimes problematic. Some systems can be extremely complex and difficult for providers to navigate. Incorrect diagnoses may be placed in the electronic medical record and easily perpetuated. This kind of error, sometimes referred to as “diagnosis momentum,” may develop more easily in electronic medical records, especially if providers are cutting and pasting data from one note to another. As we advocate for our family members in a system using electronic medical records, we need to be sure that we are not trading one problem for a different one.

Using Technology to Improve Patient Safety

Although my parents’ ability to use new technologies was decreasing, I realized that technology could help ensure their safety.

Technology can not only be useful in large, complex hospital systems but also in the patient’s home. Many examples abound: continuous glucose monitoring and insulin pumps are life-altering for patients with diabetes, apps can check for conditions such as atrial fibrillation, and so forth. Telehealth offers new opportunities for patients and providers to connect, especially in cases where transportation may be difficult.

Another example is medication dispensing services like Hero. These kinds of systems can ensure that patients receive the correct dose of the correct medication at the correct time, and also greatly reduce the stress of medication management on all involved.

Patient Safety: Some Parts New, Some Old

Our country has made amazing strides in healthcare over the past several decades. Incredible new types of medical imaging, advances in genetics, and new approaches to once incurable diseases are now reality.

Despite these advances, old-fashioned health advocacy for our family members can still play a very important role in their care. The approaches I have outlined above can hopefully help people advocating for their loved ones to stay safe and healthy. Advocates, advocacy groups, and patient advocate foundations can give a voice to patients who cannot advocate for themselves.

Remember: patient safety starts at home. We as caregivers must function as advocates for individual patients when they cannot do so for themselves. They deserve nothing less.

References

(1) Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016 May 3;353:i2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2139. PMID: 27143499.

(2) Mittal V. Family-centered rounds. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Aug;61(4):663-70. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.04.003. PMID: 25084715.

(3) Rappaport DI. What Caring for My Aging Parents Taught Me That Medical Education Did Not. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78(1):7–8. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.4454

(5) State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. https://oshpd.ca.gov/data-and-reports/cost-transparency

(6) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Navigating the Health Care System. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/1stedition/tool17.html

(7) AARP Website. https://www.aarp.org/health/medicare-insurance/

(8) Joint Commission Official “Do Not Use” List. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/fact-sheets/do-not-use-list-8-3-20.pdf?db=web&hash=2489CB1616A30CFFBDAAD1FB3F8021A5

Complex med schedule? We solved it.

Hero’s smart dispenser reminds you to take your meds and dispenses the right dose, at the right time.

The contents of the above article are for informational and educational purposes only. The article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified clinician with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or its treatment and do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of information published by us. Hero is indicated for medication dispensing for general use and not for patients with any specific disease or condition. Any reference to specific conditions are for informational purposes only and are not indications for use of the device.