Big Changes for Our Smallest Patients: Transformative Technologies for Children with Chronic Health Needs

About the Author: David I. Rappaport MD has been a Pediatric Hospitalist at Nemours/AI duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, DE since 2005. He is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College/Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He is known for his research in the care of children with medical complexity as they prepare and undergo surgical procedures.

For most families, the arrival of a new baby offers limitless possibilities - and, understandably, some predictable challenges.

This new beginning stirs emotions of love, bonding, and pride. “How wonderful! Congratulations!” proclaim cheery loved ones, friends, and colleagues. A child’s first smile, first word, first step... these are milestones that parents typically never forget. Watching a child grow and develop, learning new skills, and becoming increasingly interactive offers parents consistent positive feedback that their efforts are being rewarded.

Although pediatricians and other healthcare providers often serve as invaluable advisors for new parents, most concerns for children simply involve issues related to physiologic processes such as feeding, sleep, and behavior (such as temper tantrums, toileting, etc).

For other families, however, a newborn baby can bring challenges that they never imagined. Some of these issues may include medication adherence, healthcare costs related to long-term therapies and different medications, patient care, maintaining medication regimens for daily medication, and more.

Issues that might have initially seemed like minor physical or behavioral variations may become increasingly worrisome predictors to healthcare providers. Or worse: they become worrisome to parents but not to healthcare providers, causing tremendous parental frustration. In either case, parents––often with no healthcare experience––suddenly feel that they must become experts in their child’s condition or chronic disease, whether it is relatively common or a rarer one that even healthcare specialists may know very little about.

Combined with the fact that their child may be physically or emotionally struggling or in pain, this lack of knowledge often creates substantial stress for parents and caregivers. The stress of parents and caregivers is exacerbated as they struggle to navigate our fragmented healthcare system. Terms like “Early Intervention” and “SSI” (Supplemental Security Income)––once completely foreign concepts––may become part of the parents’ daily vocabulary. Moreover, the hardships involved in childcare, parental employment, financial burdens, establishing a care team, and care for other children may create further physical and emotional exhaustion for many parents and caregivers.

Advances in technology not only offer medical breakthroughs to parents of children with healthcare needs but also allow them to better navigate our complex healthcare system, ensuring that the child receives the safest, highest-quality care.

Who Are Children with Special Health Care Needs?

Children with chronic medical needs (often called Children with Special Health Care Needs, or CSHCNs) are an extremely diverse group of patients. CSHCNs are often defined as “those who have or are at increased risk for chronic physical, developmental, behavioral or emotional conditions and also require health and related services of a type or amount beyond that required by children generally”.1

In simple terms, CSHCNs are children with chronic medical or behavioral problems that often require a long-term treatment plan––problems that come in all shapes and sizes. A child with well-controlled asthma who takes an inhaled steroid medication from a prescribing doctor to prevent asthma exacerbations would certainly qualify as a CSHCN. So too would a child who takes Ritalin for attention deficit disorder. As would a child with a life-threatening genetic or metabolic condition.

The number and complexity of children with chronic illness in the United States is likely to increase consistently in the future. Some of these developments, like technological advances in neonatal care, may result from scientific advancement. Other contributors to chronic illness in children may be less positive; for example, our Western lifestyle will likely contribute to high rates of childhood obesity into the future, leading to increased rates of morbidity and cardiovascular disease.

How Do New Technologies Help Kids with Medical Needs?

Fortunately, recent technological innovations have transformed the care of CSHCNs, improved health outcomes and adherence rates, and reduced the need for ongoing inpatient medication therapy. These advances can be divided into several different categories:

Technology for Everyday Needs

Some children need support with their everyday needs, such as breathing and feeding. In such cases, tech innovations among medical devices can be nothing short of life-saving. These technologies include ventilators, gastrostomy (feeding) tubes, ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunts, and central lines.

Children who require these interventions are often referred to as “medically complex children.” These patients are a subset of CSHCN; they differ from children with chronic conditions like sickle cell disease or asthma, who may need daily treatments and prescription drugs but do not require the same level of support for daily survival.

Parents of medically complex children often have mixed feelings about these technologies. On one hand, they clearly help their child breathe easier, suffer fewer seizures and side effects, tolerate feedings, and feel less pain. On the other hand, these technologies come with new challenges for parents, who must now actively participate in patient education, learn how to use these new technologies, and troubleshoot any problems that may arise. For example, when can a feeding tube be safely unclogged or replaced at home? When must a patient seek immediate medical attention? Which tasks, such as feeding or suctioning, can be safely performed by a home healthcare worker and which cannot? Does a child with a central line require an evaluation with every fever (hint: yes!)? These kinds of questions can cause significant stress for parents of medically complex children.

Technology in Medication Development

Revolutionary prescription drugs have begun to offer new possibilities for the treatment of formerly difficult or untreatable childhood conditions.

For spinal muscular atrophy and cystic fibrosis, new prescribed medications called nusinersen and ivacaftor utilize a completely new and fascinating mechanism: modulating changes at the genetic level. These kinds of breakthroughs would have been considered science fiction even a few years ago but have become reality through a series of completed clinical trials. Another example is insulin pumps for patients with type I diabetes, which, when combined with continuous glucose monitoring, can greatly improve glucose management and reduce adherence barriers for these patients.

While these new approaches currently are very expensive, hopefully, these costs will decrease in the near future.

Technology in Collaborative Care

Technology can also help improve the care of children by helping better share information among parents, researchers, and clinicians.

One example is ImproveCareNow, a community dedicated to research and quality improvement in the care of children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD, which consists of Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative colitis).2 This network allows anyone with an internet connection to understand the best research and clinical outcomes worldwide about childhood IBD and to find an IBD center.

Another example is the Children’s Oncology Group, a collaborative organization that studies how to improve the care of children with cancer.3 Thanks to this work, children with acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) now have a 90% 5-year survival rate, and many can be cured.4

Case Study: Improving Medication Safety for Kids

Why Children are at Higher Risk for Medical Errors

As pediatricians are fond of saying, “children are not little adults.” Any parent or caregiver who has sought medical attention for their medically complex child at a facility without pediatric expertise will confirm this statement.

For a number of reasons, children––especially those with special health care needs––usually face higher risks for medical errors than adults.5 One classic reason for this increased risk is how medications for children are dosed. For adults, most medications have standard dosing––say, 500 mg by mouth twice per day––regardless of the person’s age, size, gender, or metabolism. Because of their significantly different size and weight, however, children typically require weight-based dosing, meaning that the child requires a certain dose per weight (usually mg of medication per kg of body weight).

In addition, the child’s dose must often be consistently calibrated over time as he/she/they grow(s) and gain(s) weight. Children are often dependent on busy, sometimes distracted adults to provide their medications while often being unable to communicate feelings of pain, hunger, or other needs. Even with the help of pill boxes, family members and other caregivers may find it difficult to adhere to a medication schedule or worse, give patients the wrong pills.

Finally, many children cannot take pills orally—they may be too young or their developmental status precludes them from doing so—so they require liquid medications. Liquid medications create additional potential for error and poor medication adherence because they require complex calculations. For example, if a 20 kg child is taking a medication that is dosed at 40 mg/kg/day:

Patient weight = 20 kg

Medication dose = 40 mg/kg/day taken twice per day

Medication concentration = 100 mg/ml

Patient dosing = 20 kg x 40 mg/kg/day = 800 mg/day = 400 mg twice/day = 4 ml twice/day

Every time the child gains weight or the concentration of a liquid medication change, these calculations must be repeated and a new dose must be given. These kinds of calculations can be difficult––even for experienced pediatric providers familiar with improving medication adherence.

Using Technology for Medication Management in Children

Beyond the technological advances outlined above, we can utilize technology to improve medication safety in children with chronic medical needs. Such technologies may not only help children survive and grow by supporting their biological requirements but can also help support their parents and providers as they navigate our complex healthcare system.

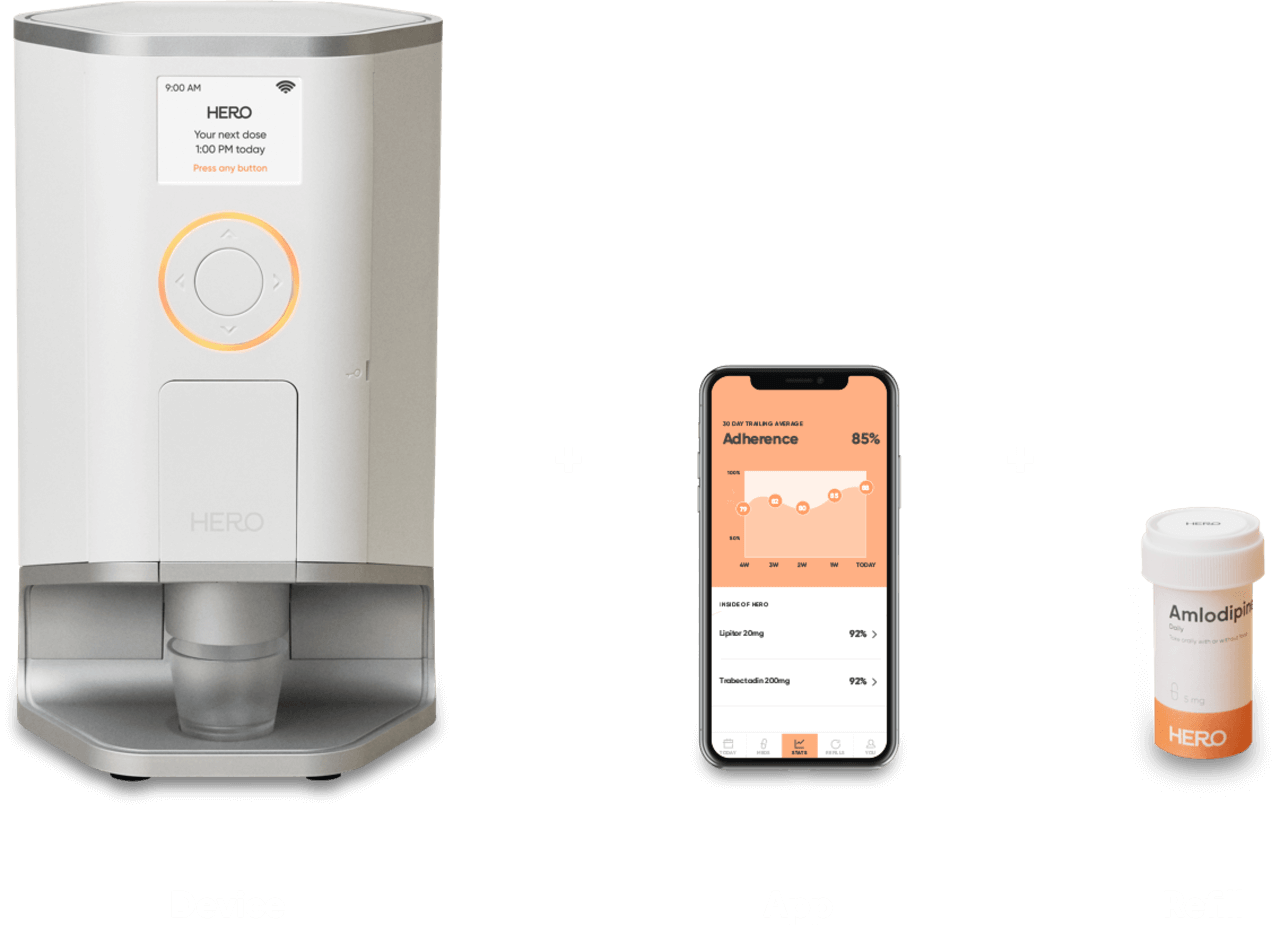

Due to their ease-of-use, technologies such as Hero can potentially improve communication among patients’ numerous caregivers to improve patient safety and patient medication adherence while also relieving their caregivers’ stress. Many children with chronic healthcare needs have very specialized approaches to their treatment, so they often require care from a number of specialists at different institutions. These institutions’ medical record systems may not communicate well with each other, creating a gap that automatic pill dispensers like Hero can help address. As the complexity of our healthcare system is not likely to change anytime soon, automatic medication dispensers like Hero could become life-changing in reducing medical errors for our most vulnerable patients while reducing stress for their families.

Future Directions

As our country hopefully refocuses our healthcare system from one that not only treats illness but also promotes health and well-being among its citizens, we will see an increased emphasis on improving value in healthcare. This means providing the highest quality outpatient and in-home care for all people at the lowest possible cost. Using technology creatively can provide significant value by reducing risks for medical errors in children with medical complexity at a relatively low cost, while also providing peace of mind for parents and caregivers. How can we put a value on that?

References

1. Children and Youth with Special Health Care Needs [Internet]. Maternal and Child Health Bureau. 2016 [cited 2020 Dec 4]. Available from: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-topics/children-and-youth-special-health-needs

2. ImproveCareNowTM. ImproveCareNow [Internet]. ImproveCareNow. [cited 2020 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.improvecarenow.org/

3. COG Homepage [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 6]. Available from: https://childrensoncologygroup.org/

4. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/leukemia-in-children/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html

5. Poole RL, Carleton BC. Medication Errors: Neonates, Infants and Children Are the Most Vulnerable! J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther JPPT. 2008;13(2):65–7.

Complex med schedule? We solved it.

Hero’s smart dispenser reminds you to take your meds and dispenses the right dose, at the right time.

The contents of the above article are for informational and educational purposes only. The article is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified clinician with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or its treatment and do not disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of information published by us. Hero is indicated for medication dispensing for general use and not for patients with any specific disease or condition. Any reference to specific conditions are for informational purposes only and are not indications for use of the device.